Cybersecurity and the rise of the autodidacts

Raise your hand if you've ever been afraid to ask a silly question.

What causes this spike in anxiety? Is it the prospect of being labelled witless, the accusation of misspent attention, or a distinct lack of confidence? Whatever the reason, I suspect this fear has been tangible for most at one stage or another.

All cards on the table, this article was initially meant to offer a guide to cybersecurity certification. - which credentials carry prestige and offer the biggest bang for your buck? Pertinent questions for the budding CISOs of tomorrow, but researching it left me feeling somewhat flat.

I will freely hold my hand aloft (again) and confess that I digressed.

You see, Google had served up a platter of 'listicles' with similar DNA. Endless pages dedicated to the 'five best qualifications, ten hottest certifications, eight best degrees and more, all of which are useful in their own right – but none added the value I strove to offer.

Having continued to tap away fervently in the quest for something more, I eventually uncovered a gem. A compelling and transformative read - Ultralearning, by Scott H. Young - dedicated to deep learning (of the human variety).

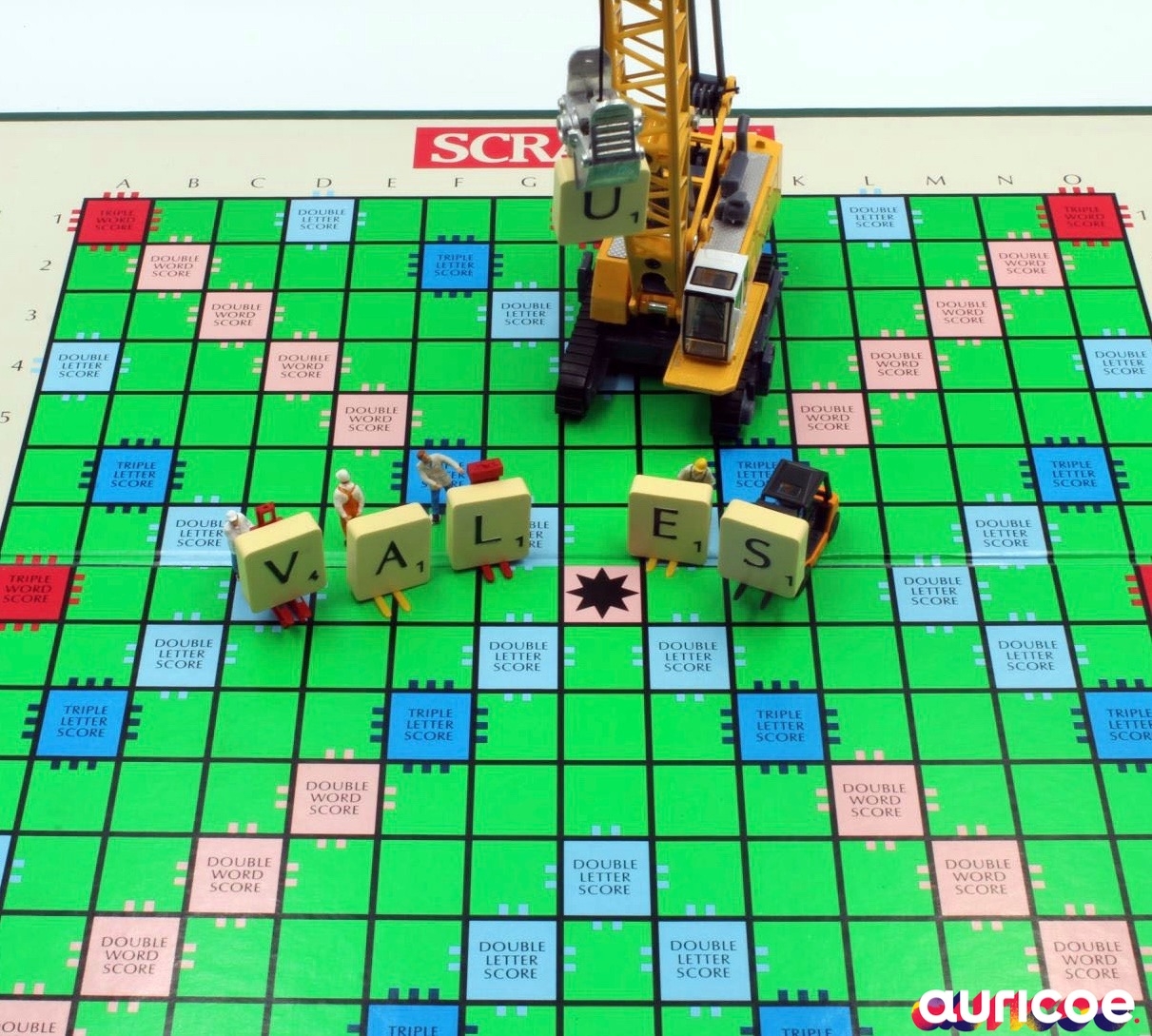

The book defines ultra learning as a strategy for mastering hard skills quickly and is bursting with impressive examples of learning feats, the knock-on effects of which, far-surpassed learner expectations – gaining fluency in four new languages within a year; near-zero experience to a finalist in the World Championship of Public Speaking in seven months; becoming French Scrabble World Champion, without speaking French, to name a few mindboggling examples. Others garnered new careers, better jobs, increased standing, and more robust networks - needless to say; it had me hooked.

As I continued to digest with interest, two points struck a particular chord when connecting the dots between cybersecurity professionals and ultra learners.

Firstly Young writes "In the words of the economist Tyler Cowen, "Average is over."…Cowen argues that because of increased computerisation, automation, outsourcing, and regionalisation, we are increasingly living in a world in which the top performers do a lot better than the rest."

"The MIT economist David Autor has shown that instead of inequality rising across the board, there are actually two different effects: inequality rising at the top and lowering at the bottom. This matches Cowen's thesis of average being over…many medium-skilled jobs—clerks, travel agents, bookkeepers, and factory workers—have been replaced with new technologies. New jobs have arisen in their place, but those jobs are often one of two types: either they are high-skilled jobs, such as engineers, programmers, managers, and designers, or they are lower-skilled jobs such as retail workers, cleaners, or customer service agents…Think of Apple's tagline on all of its iPhones: 'Designed in California. Made in China.' Design and management stay; manufacturing goes."

There is no doubting at which end of the skill-scale cybersecurity sits.

Secondly, he continued "The best ultra learners are those who blend the practical reasons for learning a skill with an inspiration that comes from something that excites them" prompting my internal RAM to load the following snippet from the (ISC)2 Cybersecurity Workforce Study 2019:

"84% of cybersecurity professionals are planning to pursue a new cybersecurity certification at some point. 59% are currently pursuing a new cyber certification or plan to do so within the next year. Their motivations for getting those certifications revolve mostly around a desire to improve in their job or to learn more. In fact, according to respondents, the top motivator for getting a cybersecurity certification is to improve or add to a skill set. Other motivators include staying competitive in the industry, advancing their career and becoming an expert. Much farther down the list is the desire to make more money."

These points combined offer suitable testimony that the Avengers of cyberspace possess the ideal mindset for ultra learning.

Waging war on cyber-crime is a relentless pursuit, made harder by the fact that it evolves at lightning speed. It requires passionate people who are devoted and inspired to draw new battle lines daily.

Leading organisations are already looking beyond red bricks, ivy leagues, and abbreviations housing the letters 'I' and 'S'. Instead, backing those with a knack for how data flows through complex environments. They seek talent that can invent solutions, without conjuring added risk, and can connect with colleagues in an analogue fashion, about digital matters.

Such qualities aren't frequently taught or easily transferred from classroom to boardroom. However, they can be honed, even perfected, when you take learning into your own hands.

Below is an outline of ultra learning's nine core principles, as described by Young, offering insight into this refreshing approach.

Principle One - Meta-learning

"The only person who is educated is the one who has learned how to learn and change" – Carl Rogers.

Meta-learning is the art of learning how you learn. The first step is thinking about the subject you aim to master and your motives for doing so. If the answers fail to convince, do not begin.

The next stage requires analysis of the critical concepts to grasp, essential facts to recall and necessary procedures to practice. Research is needed, and it is time well spent.

Once the 'why?' and 'what?' are mapped, you can consider the final piece of the meta-learning jigsaw – 'the how?'. Which are the available resources that will set you on your path, what is your optimal learning environment and who else might assist you?

Principle Two - Focus

" You don't get results by focusing on results. You get results by focusing on the actions that produce results." – Mike Hawkins

Distraction is the brain's tactic for sidestepping pain, and it tempts us all to differing degrees. Our minds use internal and external triggers - caffeine urges, hunger pangs, pop up notifications, or unwanted sales calls - as a means of swerving the tasks in hand. Mastering these triggers will make an instant, notable difference to output - they have certainly done so for me.

Assigning blocks of time to specific tasks. Setting goals and rewards to increase a challenge's fun-factor. Signalling your learning intent to others around you and nailing your colours to the mast, i.e. not letting yourself down, can all have a significant impact.

When triggers creep in, blocking them out for ten more minutes often dispels the urge. It is also useful to jot down how you feel and why. Recognising the signs and understanding that you will feel a certain way when performing similar tasks, will help you assert control over those impulses.

Lastly changing your rhetoric can reap huge rewards. If you think you procrastinate, you will. Altering that narrative increases your chances of meeting a fresh set of expectations.

Principle Three - Directness

"For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them." - Aristotle

Directness requires the marrying of learning, to real-life application.

Why is it that we download apps to learn a new language but cower from conversing with natives, and coders strive to ignite human connection, by burning the midnight oil alone? Want to deliver a winning speech? More often than not, Amazon Books trumps a crowd of fleeting listeners.

The answer – dare I say it? - is we are often afraid to venture outside our comfort zone, and this leads to the problem of transfer: how we apply formal education to everyday situations.

Forcing ourselves to employ new knowledge in a real-life context leads to a hike in confidence. You begin to spot the nuances of how these skills and abilities interact with the world surrounding them. With time you feel assured in applying them more broadly.

Learning with a project as the focus, immersing yourself in the target environment, and simulating situations where you draw upon your knowledge to make decisions, are all valuable ways to learn directly. Similarly, putting yourself in positions more taxing than those you might expect to face is a great way to tackle direct learning head on.

Principle Four - Drill

"Difficult roads often lead to beautiful destinations." – Zig Ziglar

It is impossible to grasp all facets of a given topic with equal ease. Whether born out of frustration, boredom, or mindboggling complexity, there will always be a component that slows overall progress. Single this out, pay it special attention and your efforts will bear fruit – disclaimer: I never said ultra learning was easy.

Analysing your learning as you go is necessary, but being honest with yourself is equally important. We are more likely to enjoy the things we are good at - that's human nature - so avoiding arduous tasks is easily done, and drilling draws on your motivation reserves. This is a key reason for probing how much drive you have stored in your tank at the outset.

Highlight your weaknesses and make them your strengths.

Principle Five - Retrieval

"The true art of memory is the art of attention."– Samuel Johnson

Memory and learning are closely related, but they aren't one and the same. While learning modifies future behaviour, memory recalls from the past, and recouping the ins and outs of a specific topic can be a potent learning tool in its own right.

Young writes "An interesting observation from retrieval research, known as the forward-testing effect, shows that retrieval not only helps enhance what you've learned previously but can even help prepare you to learn better… By confronting a problem you don't yet know how to answer, your mind automatically adjusts its attentional resources to spot information that looks like a solution when you learn it later."

The more complicated the recall, the better, meaning free recall tops cued recall, which in turn, outfoxes multiple choice. Alternatives to free recall include flashcards containing key points in note form. The question book method, which poses questions to the key facts that you wish to retain. Self-generated challenges, creating tasks to be solved down the line and closed-book learning, retrieving answers without searching for clues.

Principle Six - Feedback

"We all need people who will give us feedback. That's how we improve." – Bill Gates

Feedback is a stalwart member of any ultra learning campaign, typically occurring in three different forms - appreciation, coaching and evaluation.

Appreciation focuses on effort, over performance, and encourages us to keep going - less useful in an ultra learning context. Self-learners need to pinpoint areas that demand improvement and consistently analyse performance, making coaching and evaluation frontrunners in the feedback stakes.

Obtaining immediate, accurate feedback will propel your learning efforts.

Principle Seven – Retention

"Avoid tripping up down memory lane" - Me

How to make facts stick is the perennial question for educators, pupils, employers, and employees the world over. Information has a well-known tendency to slip through cracks over time, but that isn't the entirety of the problem. Bytes also get overwritten with new info, and access passwords misplaced, in the form of forgotten cues.

The good news is that there are ways to avoid the void.

• Spacing: repeating facts over a long period aids lengthy retention. Don't cram!

• Procedure: duplicating processes until they become automatic. As Young puts it "Why do people say it's ‘like riding a bicycle’ and not ‘like remembering trigonometry?’”

• Overlearning: rehearsing above and beyond the required level improves the ability to carve memories in stone.

• Mnemonics: a picture is worth a thousand words. Our brains crave excitement, welcoming new ways to recall while discounting the mundane.

Principle Eight – Intuition

"Any fool can know. The point is to understand." – Albert Einstein

When we understand the core of how a problem works, solutions take shape — experience counts in this instance, which isn't overly helpful when attempting to ultra learn, from scratch. However, Young offers pointers which help you to develop the nous for such brain-teasers.

Showing persistence, when faced with a curve-ball, is one such tip. "When you feel like giving up and that you can't possibly figure out the solution to a problem, try setting a timer for another ten minutes to push yourself a bit further…even if you fail, you'll be much more likely to remember the way to arrive at the solution when you encounter it."

Proving an answer aids understanding. Most of us think we understand how a bicycle works, but how many of us would draw the mechanism accurately? Researcher Rebecca Lawson’s study into what she calls the “illusion of explanatory depth” perfectly illustrates the difference that often occurs between what we think we understand, and what we actually understand.

Creating concrete examples of a problem lessens the issue of transfer from theory to practical application – you begin to process the problem on a deeper level. If you can't imagine a suitable example, this more than likely signals a gap in aptitude.

Finally, don't fool yourself. The more you learn, the more questions arise. Young correctly points out that the reverse is also true. "The fewer questions you ask, the more likely you are to know less about the subject".

Contrary to the old adage, if a silly answer is what you fear, it’s highly unlikely what you’ll get. Quite the opposite in fact. Responses often fill the additional, less apparent holes that permeate knowledge.

Do not stop asking questions.

Principle Nine – Experimentation

"I can never find the thing that does the job best until I find the ones that don't." – Thomas Edison

Having studied pharmacology at university, the idea of testing a theory by working through a method, analysing results and forming a conclusion is far from alien, despite the decade (or two) that have since whistled past.

In the case of ultra learning, doing so with vigour and intensity, before sampling a new technique or style, is what sets it apart.

This brand of experimenting transformed van Gogh from being an 'unskilled' artist, who started late, with little talent for drawing; to one of the most famous painters of all time. Vibrant swirls of colour, applied in impasto fashion, with sharp outlines, were all a far cry from his initial trademarks, and – I strongly suspect – a result of his tenacity and drive to develop as an artist.

As we transition through the learning gears, from novice to proficient, and on towards mastery, many disciplines honour originality – it is hard to show flair without the thrills and spills of experimentation.

Conclusion

"Don't count the days. Make the days count" – Muhammad Ali

In summary, the nine principles of ultra learning are meta-learning, focus, directness, drill, retrieval, feedback, retention, intuition, and experimentation. Applying this focused and personalised way of learning will enable you to amass highly relevant skills quickly – real-world expertise.

Cybersecurity readiness is now not only a choice but a business decision, for those companies leading the charge against cybercrime. These organisations are already clamouring for voracious self-learners - autodidacts – some, seeing the boundless enthusiasm that sets this draft apart, and others, spotting mosaics decorated with unique skills and abilities that combine to form the indispensable.

I can think of worse reasons to give ultra learning a go.

Professional courses and qualifications will always have a role to play, and thankfully they elude the incessant grade inflation debate that scorches the academic landscape each summer. But learning of the 'ultra' persuasion, is not an either-or scenario. You can treat it like any other scholastic resource, with one significant difference – you have complete control over your learning, without the pressures that arise from formal study, financial or otherwise.

The process requires organisation, but it doesn't have to be a full time exploit. It can take the form of part-time projects, or even simply involve reinventing the way you currently learn.

At the most basic level, learning a new skill is fun. It gives us a sense of pride, improves our creativity and makes us happy — all of this at a point in history where it's never been easier to teach yourself.

To the CISOs of the future, I ask the following. What new skills could you offer an organisation if you took the right approach to make them successful?

Who might you become?